Palazzo Sessa

Opere della Collezione Agovino

Text by Francesca Blandino

04.10.2014

Collecting. Recreating AN IMAGE OF The World.

Every language is an alphabet of symbols whose use presupposes a past that the partners of a dialogue share. But how can you understand the infinite Aleph that my trembling memory is hardly able to perceive?

(Jorge luis Borges, El Aleph, losanda, Buenos Aires 1952; Ottmar Ette, Literature on the Move, trans. katharina Vester, Amsterdam and New York, rodopi, 2003)

In a collection, no one item is more important than the others; they all have the same value because what matters is not their appeal, but their uniqueness. In fact, the uniqueness of an object is in the eye of its collector, although this is virtually impossible. To focus on the relationship between the collector and his/her collection means to delve into the deep chaos of his or her memories. Each passion is inextricably linked to the most remote places of one’s memory. In a collection, the value of each object is given by personal criteria that are inexplicable, irrational, dreamy, and emotional, regardless of the collected object. like dancing in a constellation of thoughts, collected items converge in the intimate universe of the collector, the essence-guardian of their destiny.

Gilles Deleuze stated that the work of art is the only thing able to resist death, because it holds the act of creation, which is the first act of resistance. Owning artwork is undeniably a way to have power over time and reality: it is an action that creates new possibilities of meaning of the world and the self. Since the advent of technology, the work of art has lost the aura it originally had, becoming a truth-detecting tool, generating new visual perceptions able to alter the stream of consciousness of individuals and the masses. Art discovers the world, it illuminates it and at the same time preserves its deeper truth, which is revealed only to those who are open to imagination. It reveals truths which are not eternal but historical, truths that are not absolute but that keep unfolding. When experienced, the practice of art can break the link of the usual and obvious. The collector of art works is driven by the desire to break away from the usual and to empathize with the work itself to change his/her relationship with the world.

According to Goethe, to err can mean to make mistakes but also to wander, to follow the incessant motion that is key to new discoveries.

In Faust we read “Man still must err, while he doth strive,” addressing an individual forever in search of the meaning of things. like a dowser,

the collector seeks works that he/she takes possession of to live and understand the eternal present which they bear, even for a few moments. The Agovino Collection is the other side of the mirror for Fabio Agovino, a collector determined to indulge his inner need, an uncontrollable compulsion to express the objective element of his own world. Art acts as a vehicle of communication between the real and the unconscious, and its task is to convey the revelation coming from inner spirituality. Fabio sees the world through the eyes of those who are aware that the sense of things is drawn from within. The visual perception of reality is not a mechanistic process, it is a sum of feelings and visions that capture the unity of the outside world as it appears from one’s interiority, in a total lack of objectivity. The work collection is for Fabio the physical expression of his desire to turn art into the key to interpreting the universe.

The origin of collecting basically stems from the need to understand the world intellectually. The first collections are found in the wunderkammern or “cabinets of wonders,” rooms popular in late sixteenth-century stately mansions, born as places where to collect rare and bizarre objects, whose purpose was to arouse astonishment. The wunderkammer was a kind of private museum of the aristocrat and the sovereign who, through their collections of precious and unusual objects, showed their power. recreating a microcosm representing the world was the main intention of nobles and scholars of the time; in fact, the collected objects had to do with natural history, botany, zoology, alchemy, and later also art. Collecting is an act that tries to meet the need for knowledge starting from inner chaos. The figure of the collector straddles between order (external reality) and disorder (interiority) in their endless dialectic tension. The search for a possible balance between these two poles produces a constant renewal of the value of the collected objects, which with each addition, every relocation, every enumeration, take on a different meaning. The deepest instinct of a collector, i.e. his/her desire to acquire new pieces, is connected with the desire to regenerate his/her own collection, through which he/she comes closer, piece after piece, to his/her hidden truth. The Agovino Collection also stimulates the intellection of its creator, who establishes a direct contact with the work as it becomes ‘other’ than its simple form, becoming the bearer of different views on things. Fabio pours his inner chaos into art which in turn, breaking down the wall between past and future, opens his eyes to the many visions of an only apparently static and indecipherable present.

The Agovino Collection is housed in the historic Palazzo Sessa a Cappella Vecchia, located in the San Ferdinando district in Naples. Currently made almost invisible by the proliferating city buildings, Palazzo Sessa is a remarkable building, rich in character. home of prominent figures, it has very old origins. Celano says that the palace was built on an abbey, Santa Maria a Cappella Vecchia, which in turn was presumably built on the hellenistic temple of Serapis. The portal is dated 1506. After the suppression of religious orders, the building was purchased by the Marquis Giuseppe Sessa and became the headquarters of the British embassy. From then on, many famous people lived in the building. In 1787, it was the turn of Goethe, on a visit to Naples to meet lord hamilton, the British ambassador to the kingdom of Naples from 1764 to 1800, known to be an avid art collector. The collection is now actually housed in one of the rooms of hamilton’s house, according to the principle that art is an essential element of those seeking a vision beyond the surface. Palazzo Sessa is currently also the premises of the Jewish Community, as shown by a 1928 plaque. It was the rothschilds, in 1864, who contributed to the transformation of one wing into a synagogue. Fervor and cultural forces are stratified in time in this beautiful palace, located between the restless sea and the unrelenting presence of the upper town.

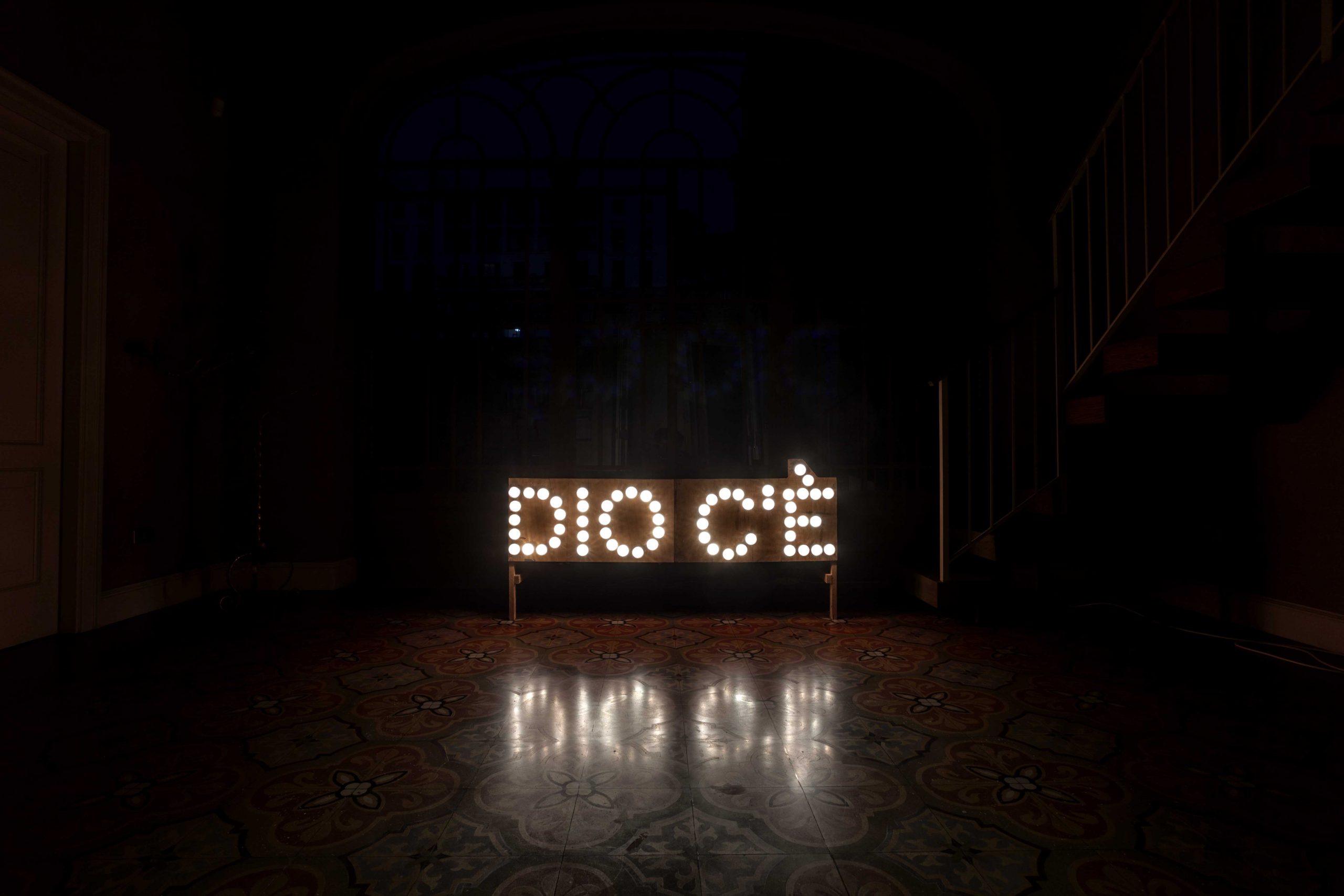

The exhibition Dio c’è. Opere dalla Collezione Agovino [God Exists. Works from the Agovino Collection] consecrates the dynamism of Fabio’s collection, in which he tries to investigate the “difficulties in making sense” that pervade everyday existence. let us start with the title.

Dio c’è comes from the work of the same name

by Claire Fontaine, a collective born in Paris in 2004, whose name refers to a famous brand of French notebooks, and that uses art as a device to generate subversive thoughts on models of power through the use of the ready-made. Dio c’è is not an evocative utterance, it is the statement found on the walls of Naples and other cities in southern Italy to point out drug-dealing areas. Claire Fontaine writes the statement in neon, giving it a brightness with sacral qualities. The overthrow of the status quo of social systems becomes possible with displacements of sense, decontextualization and linguistic machinations. Dio c’è is a form

of rebellion to immobility caused by the power that influences desires and shapes lives to fit the strategy of capitalism. The exhibition is an invitation not to stop looking for one’s uniqueness in the multitude of spectacularized goods and fetishized bodies.

The denunciation of power and its ability to turn amusement and knowledge into tools to control bodies is veiled in the work Subjects (Chaos) by Thomas Hirschhorn, whose artistic practice aims at undermining the idea of a perfect world given by the media. his mannequins dress clothes are made of many different materials –plastic, aluminum foil, adhesive tape, photographs, etc. – as if to encompass in a single entity all the randomness and precariousness of reality. Hirschhorn is obsessed with finding a form that, going beyond the significant comprehension of the first meeting, is capable of renewing itself at every new glance.

The relationship between reality and representation is investigated by Patrizio

Di Massimo, who for Dio c’è presented the performance Mister, a pile of pillows leaning on a wall, with parts of a human body buried in the pillows sprouting from within. The artist tries to create a separation between reality and truth, using devices like irony and shifting points of view, starting from the interpretation of historical identity. Allusive, surrealism-inspired games animate his creations, appearing as videos, drawings, installations and performances. How to recount things is the starting point for the investigation of the concept of identity, since the purpose of the artist is to show the different ways in which the construction of historical events meets rhetoric.

Getting lost in a maze of narrative suggestions focused on the past is a common thread that connects the works of Tris Vonna- Michell. his installations, as in the case of Ulterior Vistas, follow a circular motion of sense, which leads every story, every narrative reconstruction, to be repeatedly renewed. Space, fortuity and time change visual perceptions and at every change establish the criteria for the continuous reworking of stories. The viewer is left with the task of seizing the multiple perspectives of meaning, engaging with the space created each time by the artist.

The search for a logical interpretation of historical events is also found in the installations by Simon Denny, an artist interested in the changes brought by the irruption of technology in everyday life. The language generated by the media, like slogans and marketing strategies, and the widespread use of digital and mechanical devices have produced an unbridgeable fracture in the concept of innovation, while undermining the very premises of the history of art. how dutiful is it for institutions to preserve works of art made with materials with a short life cycle? In contemporary reality, we witness the prevalence of the ephemeral that comes to terms with obsolescence, which has become stronger due to the power of the market. Hic et nunc applies to objects and bodies. Thus, a question arises: how can we safeguard preciousness from the disease of uncertainty? Seth Price suggests vacuum- preserving what is more valuable to us, thus freezing it and turning it into an icon, the way he does with his Vintage Bomber pieces.

The journey in search of a sense of things continues in the path of Dio c’è, expertly orchestrated in all areas of the Agovino home,

bar none, not even the most intimate. Each work is a mirror of the next: meaning is revealed in the relationship that is established with each work. hence, May hands’ naive lightness meets Nico Vascellari’s material impetuosity, Darren Almond’s minimalistic existentialism dialogues with Cheyney Thompson’s reinvented everyday life, Erica Mahinay’s varied and colorful production converse with the emotion and irony of Grear Patterson, who appropriates the language of the media system to take it apart and uncover its hidden mechanisms. And so on. The arranging, sorting and the resulting combination build the narrative of the exhibition. Selection and combination save the work from indiscriminate accumulation since each element finds a connection with the space that hosts it and establishes an emotional connection with the other elements. Fabio constantly rearranges the works, classifying them always differently but in close connection with his memory, in order not to lose the iconographic and cultural legacy he has collected.

Dio c’è is an exhibition of the potential, the possibility of creating multiple relationships and build infinite meanings of reality. The fear of not being able to find a representation of one’s order, or not to find an order at all, vanishes in the presence of an open narrative which allows for the retrieving of the invention in addition to enumeration, originality in addition to quotation, freedom beyond memory, spirituality in the world, and meaning for things.

Photos by Maurizio Esposito